S

SEC Sports

Ticket sales tumble as Missouri football tries to keep up

According to NCAA reporting documents obtained by the Missourian through an open-records request, the number of tickets scanned for Missouri's seven home football games in 2018 was 24,377 per game,

ABOUT THIS SERIES: More than seven years after MU uprooted its elf from the Big 12 Conference, the Missourian examines whether one of the biggest decisions in the university’s history has met expectations. In this series, we explore the benefits — and drawbacks — of the school’s move to the Southeastern Conference.

As a rain-soaked CBS Sports broadcast camera panned across a small sea of ponchos in Missouri’s Memorial Stadium moments before kickoff against SEC rival Arkansas last fall, a staggering number of empty seats were visible. It wasn’t particularly surprising considering the 20 mph winds and half an inch of rain that poured on Columbia. The fans who did show up — the stadium looked half-full at best — watched as the Tigers dismantled the Razorbacks 38-0 on senior day.

The attendance announced that day was 52,482. According to Missouri’s own records, though, there were fewer than half that number of people there, despite head coach Barry Odom buying and giving away nearly 5,000 tickets in advance of the game.

Woeful weather and the beginning of fall break, when most students have already left campus, isn’t typically a combination that lends itself to strong attendance. But the number of people actually at Memorial Stadium that day was no one-off fluke. According to NCAA reporting documents obtained by the Missourian through an open-records request, Missouri’s actual average attendance for its seven home football games in 2018 was 24,377 per game, or roughly 47 percent of what the school reported in its game box scores.

Athletic department officials, however, say the numbers they reported to the NCAA aren’t a full picture of the actual ticketed attendance in the 2018 season because faulty scanners, which were sensitive to the elements, and poor Wi-Fi connectivity forced event staffers to move large swaths of fans through the gates without recording their tickets into the system. No estimate was available for how many unscanned tickets were allowed into the stadium.

Nonetheless, an artificial inflation of attendance numbers isn’t unusual in college sports. Far from it, actually. Across the country, the number of tickets being scanned at college football stadiums is about 71 percent of the attendance you see in a box score, according to The Wall Street Journal. In some cases, there might be a reason for schools to fudge their attendance numbers beyond the obvious desire to make it seem as though there were more people in the stands than were physically at the game: To stay in the NCAA’s top division, schools are required to maintain attendance of above 15,000 per game — ticketed or announced — over a rolling two-year period.

There is no concern of Missouri coming close to that number with its own attendance, but like nearly all other FBS schools, the athletic department bumps its numbers by also including game participants, band members and media in its announced attendance.

“We track the tickets sold, so from a budget standpoint, we know where we’re at,” said Nick Joos, Missouri’s deputy athletics director. “For us, that seems to be more consistent with what our peers are doing nationally.”

Following a trend

The Southeastern Conference doesn’t issue attendance guidelines to its member universities, a conference spokesperson said, and according to the NCAA’s Statistics Policy and Guidelines, schools can record attendance in three separate ways: turnstile count (the number of people who actually come into the stadium), the number of tickets sold or estimates made by a staffer during the game. In a 2017 survey by The Kansas City Star, to which only eight SEC schools responded, each said they use the number of tickets sold to report their attendance.

In the SEC, seven schools that responded to the Journal’s records request reported that the number of tickets actually scanned was more than 70 percent of the announced attendance, with Tennessee (88 percent) and Missouri (83 percent) having the most accurate reports. Ole Miss and Arkansas each reported that actual attendance was below 60 percent of what they had announced, and five schools (Mississippi State, South Carolina, LSU, Vanderbilt and Georgia) said they had invalid counts, don’t keep scanned ticket numbers, didn’t respond or are exempt from responding to public records requests.

The difference between Missouri’s announced and actual attendance was between 15 and 18 percent for the 2016 and 2017 seasons, but that difference nearly tripled in 2018.

Missouri still received ticket revenue from its original sales, even the nearly 190,000 that didn’t get scanned, but revenue from in-stadium sales are almost guaranteed to be affected. Rob Sine, who served as the president of IMG Learfield, Missouri’s outbound ticket sales partner, told the Journal that not only does attendance drive things such as recruiting and donations, but if fans don’t use their tickets, they’re less likely to keep coming back.

“You lose concessions and merchandise, but I also think you lose the home-field advantage that you want,” said Jay Luksis, Missouri’s executive associate athletic director for marketing and revenue generation. “We’ve seen it a lot here lately where we’re either up big or we’re behind, and there hasn’t been a ton of close games in the three years I’ve been here. ... And we need to do everything we can to entertain them while they are here because obviously we want them to stay. But sometimes it’s tough to compete with parties and restaurants and bars downtown, and also with TV.”

Revenue going the wrong way

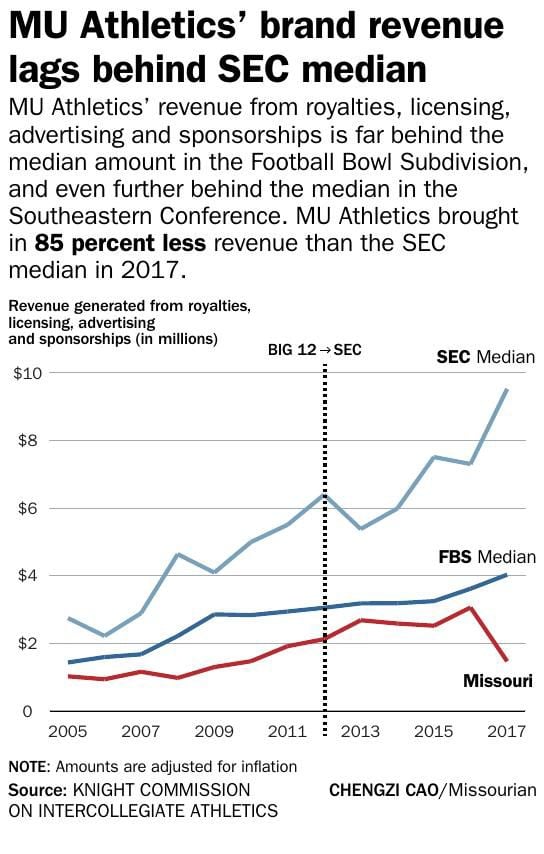

Missouri’s contracts with in-stadium sponsors and advertisers, as well as revenue from royalties and licensing, aren’t directly affected by attendance numbers, Joos said, but Missouri’s revenue from those sources has dropped by more than 40 percent from 2014 to 2017.

Financial reports aren’t available for the 2019 fiscal year, but in Missouri’s 2018 reports, which included the 2017-18 football season in which Missouri’s average ticketed attendance was just over 42,000 per game, the athletic department generated just $1.5 million in revenue from those sources — $18 million less than SEC-leading Texas A&M and at least $10 million less than five other SEC schools.

As a result of the declining ticket numbers, Missouri recently announced substantial price cuts for 2019 in hopes of drawing people back to the stadium. According to the school’s ticket office, prices will remain the same or drop for 85 percent of tickets, and fans buying season tickets are expected to save $132 per seat under the new pricing plan. At the same time, student season ticket prices dropped from $260 to $150 after sales decreased by nearly 33 percent from 2017 to 2018.

“We’re really taking the approach of, we need to get people back in the seats, even if we take a little bit of a hit with revenue,” Luksis said. “The goal is obviously higher quantity to equal out the revenue.”

Missouri’s athletic department, like many of its peers, faces an uphill climb in getting people back into the stadium. Over the past four years, college football attendance has declined by more than 7 percent nationwide, and that’s simply using the announced attendance numbers. In 2017, the SEC, which led college football in attendance for the 20th consecutive season, saw its average attendance decline by 2,433 fans per game — the league’s biggest drop-off since 1992.

Through its media rights contracts with CBS and ESPN, which owns the SEC Network, the conference has more football games nationally televised — and more revenue from those televised games — than ever before. But it also must reckon with the options those broadcasts provide to its fans. They no longer have to come to the game to see their team play, and depending on cost, weather, traffic and ultimately their physical place in the stadium, watching from home is often more convenient and cost-effective.

“It’s a technology issue,” Football Bowl Association executive director Wright Waters told CBS Sports. “The public is ahead of us every day in what they can get from technology. We have not been able to keep up.”

Turning the tide

To combat the declining attendance and revenue numbers, Missouri has turned to alternative methods of getting fans in the stands, including a yet-to-be-announced partnership with local business owners that would “bring and engage their employees to help fill the stadium,” Luksis said.

The school has also placed a substantial bet on premium seating with the addition of the $98 million South End Zone Project, which is expected to be completed before the Tigers’ 2019 home slate begins Sept. 7. But the success of those sorts of financial undertakings, which are relatively new in college football, will be determined in the coming years. Ultimately, much like it does at other universities not named Alabama or Ohio State, bringing back fans — and their money — comes down to winning games and being consistently competitive at the top of the league.

“It was a few short years ago that we were there,” Luksis said. “Those were SEC East-winning teams going to great bowl games, and people were still excited about the move to the SEC; that kept ticket revenue up for a while. Obviously team success goes into it, and we’ve had a couple good years in a row. I fully believe it’ll be even better going into next year.”