The undefeated Georgia Bulldogs rank No. 1 in the AP poll ahead of Week 7 of the 2021 college football season, and it's due in no small part to a defense molded by Kirby Smart.

www.pff.com

The path to a

college football title ends in Indianapolis this season, but all roads must go through Athens, Georgia, and the best collection of 11 players in the sport.

Georgia's defense stands not just as the class of 2021’s college football season, but it also knocks on the door of historic greatness in an era of more space, yards and points than we’ve ever seen. The Bulldogs currently rank first in

PFF defensive grade (94.8),

pass coverage grade (94.9) and expected points allowed per play (-0.451).

| Defensive Grade | Run-Defense Grade | Coverage Grade | Pass-Rush Grade | EPA/Play Allowed |

| UGA Defense | 94.8 (1st) | 91.4 (3rd) | 94.9 (1st) | 88.7 (6th) | -.451 (1st) |

The last decade (plus) of college football has been a case of trial and error in defending the advent of the spread. Many defensive minds have had their share of sunshine and twilight periods.

Click here for more PFF tools:

Rankings & Projections | WR/CB Matchup Chart | NFL & NCAA Betting Dashboards | NFL Player Props tool | NFL & NCAA Power Rankings

For years, Gary Patterson laid claim to the most flexible defense in the sport, Brent Venables’ current tenure peaked as what looked to be the

Alabama antidote, Pat Narduzzi’s old-school Cover 4 helped build

Michigan State into a contender and Bud Foster was all but guaranteed to kick dust in the eyes of an ACC championship hopeful. Dave Aranda, Jim Leonhard, Todd Orlando, Jon Heacock and Marcus Freeman are all 3-4 coaches who have introduced their only flavor of containing explosive offenses in this wide-open era.

In these ranks stands Kirby Smart, a coach from the most decorated tree in college football. Before Lane Kiffin came by to revolutionize the way Alabama played offense, Smart worked on the stifling Crimson Tide defenses from the beginning of Nick Saban’s tenure until 2015.

Between each of these names are a variety of schematic approaches — from man-to-man to three-high zone safeties, even and odd fronts and disparate levels of talent. However, the one thing that’s almost universally held between each of these signal-callers is the ability to blitz the spread.

While no one would be foolish enough to claim that any of the Alabama defenses fell short of greatness, it felt that the best offenses were creeping closer to drawing even. By Smart’s own admission (at a 2019 coaching clinic), the sentiment in the coaching offices at Tuscaloosa was that they were “slipping.”

When Smart left to take over at Georgia, he knew better than to reinvent the defensive wheel. However, newer approaches to stopping newer offenses needed the space to be accommodated within his schemes. The way the staff recruited its front seven had to be changed, and the coverage concepts and the way the defense played up front needed tweaking.

Winning at the highest levels will always come down to having the

right good players in place, but just rolling out 11 athletes can create issues (I’m looking in the direction of Columbus, Ohio). I think there have been faster, and outright better, defensive players at Georgia prior to 2021, but what we’re breaking down today is a scheme much more interested in

attacking the spread than defending it.

Complete

this survey to test PFF’s soon-to-be-released app!

SAFE PRESSURE ON EARLY DOWNS

Nobody outside of the coaching world is much interested in hearing the axiom anymore, but a great defense beginning with stopping the run isn’t any less true today than it was three decades ago.

Shrinking the call sheet for an offense requires winning on “mixed” downs — first down and second-and-normal (1-7 yards in distance) — and forcing obvious passing scenarios. Nobody is better at winning early than the Bulldogs, ranking first in defensive success rate on early downs, at a 60% clip.

| Defensive Success Rate | EPA/Play Allowed | Defensive Grade |

| UGA, 1st & 2nd Down | 60% (1st) | -.448 (1st) | 93.7 (1st) |

In the era of the two-back offense, defenses tried to make plays in the backfield with blitzes called “fire zones,” attacking with five players but keeping zone eyes in the defensive backfield for run support instead of playing man coverage.

With spread offenses in general and the RPO, in particular, investments in sending five defenders can be expensive. Chances are a defense will find more tackle-for-loss opportunities, but it comes at the cost of a player in coverage to sit in the windows of high-percentage throws underneath. Taking those away while rushing five requires a defense to play man coverage, thus landing a unit right back at square one of the quandary facing Smart and Saban in Alabama.

How then can a defense, in the era of the spread, maintain exceptional production against the run without it coming at the expense of its ability to cover the pass?

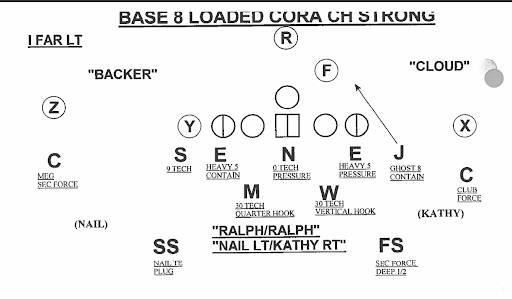

A (somewhat) novel concept of the “creeper” has come to light as the 3-4 defensive structure finds new wings in this time of football. A creeper, by design, is using a player at the second level (slot corner, inside or outside linebackers) to be the fourth rusher by blitzing from “depth.” In some designs and out of certain fronts, a traditional-looking rusher can drop out into coverage.

A creeper, in essence, is the happy medium between blitzing to create pressure or tackles for loss without it coming at the expense of a defense's coverage flexibility. This, in my eyes, stands as a direct parallel to the run-pass option and play action on the offensive side of the ball, creating a best-of-both-worlds play call.

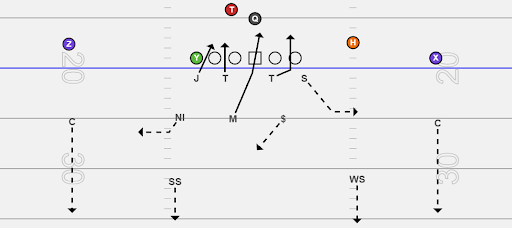

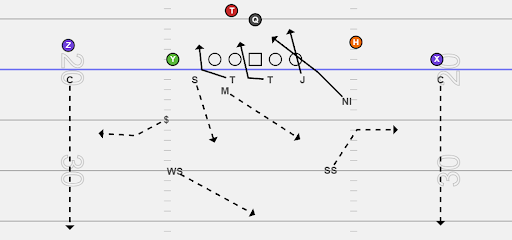

In this example against Arkansas, Georgia is giving the presentation of a four-down, old-school, Cover 4 defense. On the indicator that the snap is coming, the middle linebacker creeps down and blitzes through and across the center’s face, and the edge defender (the Sam, in this example) would be “dropping” out to wall the curl area if it were a pass play.

With the ball being handed off, the effect of a five-man pressure is there for the defense, and Georgia is able to get a run fit akin to what would be a typical Cover 4 call out of its base package. The middle linebacker effectively is running through his run fit similar to what the nose would do if aligned over the top of the center.

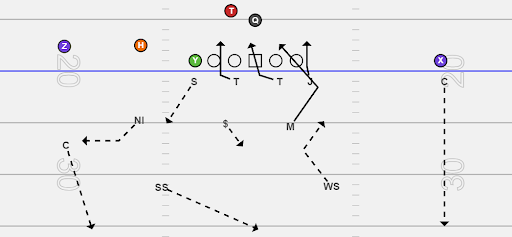

In the next example, Kirby Smart and defensive coordinator Dan Lanning call to bring an edge creeper away from the trips side of the formation. Again, because the play is a designed handoff, Georgia gets the effect at the point of attack of rushing five without taking a player out of coverage, allowing the defense to play Cover 3 had it been a pass.

Mixing in these creeper calls with their ability to line up in even and odd fronts and play the run straight up is a major factor in this defense recording a defensive stop on 79 of the 114 run-down snaps it faced and a top-five average depth of tackle at 3.26 yards.

In these two clips, not only is the defense able to make plays at or behind the line of scrimmage, but an important piece of playing elite coverage on early downs is protected, and that’s the disguise of a two-high safety shell no matter what the call.

This means quarterbacks can’t get a clean look at the rotation of the defensive backs or a man/zone giveaway until after the ball is snapped. With second-level defenders flying upfield as blitzers, creating the impression of pressure, quarterbacks are fooled into looking for their hot throws and finding nothing open underneath.

SIMULATING PRESSURE ON CONVERSION DOWNS

| Defensive Success Rate | EPA/Play Allowed | Defensive Grade |

| UGA, 3rd & 4th Down | 68% (5th) | -.459 (4th) | 85.2 (3rd) |

Using creepers on early downs against the run helps to puncture the “bubbles” in the defensive front (the areas defensive linemen aren’t occupying), but creating the impression of pressure pays just as many dividends in attacking pass protections, if not more.

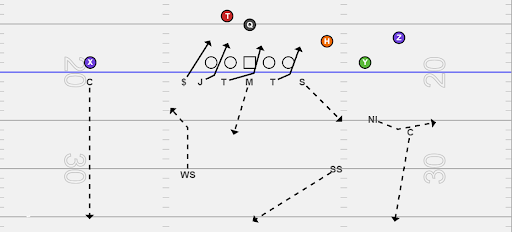

In the first clip against UAB, Georgia is presenting two different worlds: an all-out blitz look (to the offensive line) and a two-deep shell (to the quarterback). The desired effect is to get the quarterback and offensive line looking in the same direction, where it appears all the pressure is coming from.

The defensive line stunt and the dropping linebackers will occupy the linemen sliding toward the bluffed pressure, buying time for the twist happening on the quarterback's blindside. This isn’t dissimilar from all the picking and twisting you’d see in the NFL, and college defenses need these bluff looks to buy enough time for the defensive line twists and slants to work into open areas.

A threat is only as good as one's ability to carry it out in reality, and against Vanderbilt, that loaded-up front wasn’t a decoy to bring pressure from the opposite side. The Commodores' quarterback and running back have a miscommunication on who the potential unblockable defenders are, and it results in easy pressure.

Masking safety rotation to throw some changeups in coverage behind these pressures is a great way to trap the quarterback into regrettable downfield throws. Georgia comes one stride short of intercepting a bullet from

D.J. Uiagalelei on a simulated Cover 2 pressure, sitting right in the area of the intended route.

I think, too often, we discuss offensive innovations without giving much thought to whether a philosophical counterpunch even exists on defense. Offenses can change their cadence, and defenses can move/stem the front (something else Georgia is excellent at) and draw linemen offside. Different formations create additional gaps and spaces, and certain fronts eliminate them. There are a multitude of answers for the concepts you see from the best offenses in the sport.

For Kirby Smart, a coach who grew up, played and coached in an era of football tailored toward stopping a two-back offensive philosophy, the spread afforded offenses answers that defensive coaches simply weren’t prepared for. What Smart and other elite defensive coaches have found is a way to continue attacking offenses without endangering their coverage players.

Because of that, the Georgia Bulldogs are championship-ready, and their 2021 defense may become the new gold standard in stopping the modern offense.