planomateo

Member

Left out: How Larry Scott and the Pac-12 continue to lose ground in the college football arms race

Updated Nov 27, 10:41 PM; Posted Nov 27, 8:58 AM

Pac-12 Commissioner Larry Scott has the sweetest administrative compensation package in all of college athletics at $4.8 million a year. (File Photo by Christian Petersen/Getty Images)

By John Canzano

The Oregonian/OregonLive

SAN FRANCISCO -- The seven-story building located at 360 Third St. in downtown San Francisco has large glass doors, plenty of natural light and a landscaped rooftop deck. It lies within a walk of AT&T Park, in the heart of the technology world, on the one of the most expensive commercial real estate footprints in the country.

The Pac-12 Conference headquarters occupies more than 100,000 square feet on the third and fourth floors. The studios for the Pac-12 Network are here, as well as the Centralized Instant-Replay Command Center.

The conference moved the operation here in 2011 with the aim of growing a television network, boosting revenue and seizing the synergy with the tech industry. The vision wasn't just to keep pace in major college athletics, but for the oft-overlooked conference to accelerate to the forefront using the Bay Area as a launch pad.

In the process, the headquarters became the 13th member of the conference.

From officiating issues to high operating costs to being left out of the College Football Playoff for the second straight year, the Pac-12 Conference is facing a multitude of problems. This is part one in a four-part series that takes a deeper look at what is ailing the conference.

League executives will tell you the plan is a success. They say the conference is competitive now, and well positioned for the future. But fans know better, and internal records tell a more complicated story. The financials of the Pac-12, when compared to its peers nationally, paint a picture of a conference that is operating lavishly and producing significantly less revenue for its members.

The lightning - or lightning rod - behind the conference's dramatic transformation is Commissioner Larry Scott, a 53-year old former Harvard tennis player.

Conference insiders cast Scott as whip-smart and a scary-good negotiator. Others say he fosters a totalitarian culture, revels in the luxurious perks of his job, and uses his shrewd negotiating tactics in ways that harm the conference itself.

"Larry is a lavish guy; he likes extravagance," said Bill Moos, the former Oregon and Washington State athletic director, who is now at Nebraska. "He runs the Pac-12 like he's the commissioner of Major League Baseball."

The Pac-12 Conference touts itself as "The Conference of Champions" and it wins titles in sports such as cross country, track and field, gymnastics, baseball and volleyball. But the conference hasn't registered nationally where it counts most in college athletics -- football.

In fact the Pac-12 feels further away, maybe than ever, to mattering on the national stage in the biggest revenue-generating sport in college athletics.

Last season, Scott's conference went 1-8 in the college football bowl season. It marked the worst postseason performance by a Power-Five Conference in history. The Pac-12 will get shut out of the College Football Playoff for the second straight season. And there are questions about the cost of doing business, and whether Scott has the Pac-12 positioned to keep pace with its peers.

Was moving the longtime Bay Area headquarters to its high-rent location a wise move for the conference -- or a Scott misfire that now haunts the football programs?

"All of our eyebrows went up a little bit when the conference moved from Walnut Creek to San Francisco," Moos said. "There's a reason ESPN is in Bristol (Connecticut) and not Manhattan.

"But Larry likes to go first cabin."

Has it been worth it? And if not, who's to blame? Scott? His bosses, the university presidents? Or Pac-12 Conference fans themselves? Depends on who you ask.

---

Rick Neuheisel left last year's college football bowl season concerned about the Pac-12 Conference. The former Washington, Colorado and UCLA coach saw something alarming.

It wasn't just that dismal record in the Pac-12 bowl season. It wasn't just that Penn State beat Washington in the Fiesta Bowl and Ohio State blasted USC in the Cotton Bowl. Or that the Pac-12 got outscored by a combined 87 points in the nine bowl games.

Neuheisel's biggest concern was the shrinking size of Pac-12 players.

"The size disparity was ridiculous," Neuheisel said. "We, as a conference, have to get bigger. We play in this league that is small, skilled and make all kinds of plays, but we don't look the part physically. We don't have the ability to recruit and have the bells and whistles because the money isn't coming in as it should."

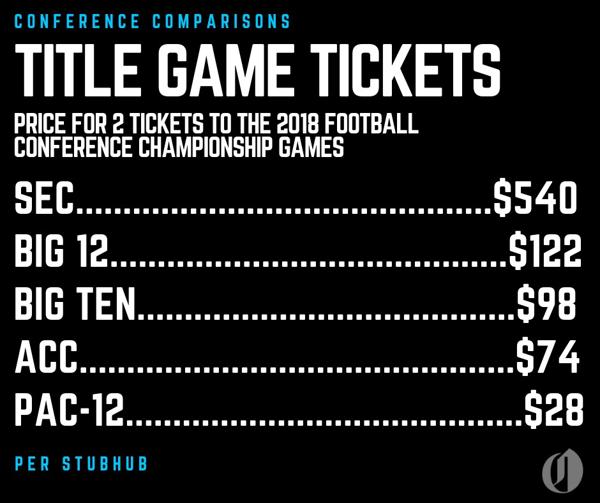

Here's what each conference distributed (per university member) in the last reported tax year:

SEC -- $41 million.

Big Ten -- $37 million.

Pac-12 -- $31 million.

Neuheisel has the lack of economic parity pegged. But what he and some others don't know is that the Pac-12 Conference isn't just distributing less to its members, it's also spending at a higher clip in key categories such as office rent, executive-team salaries and travel.

That popular SEC motto "It Just Means More," could add, "It Also Costs Less."

Scott negotiated the sweetest administrative compensation package in all of college athletics for himself: $4.8 million a year.

Don't blame Scott for that. Blame his bosses, right? Scott, who came to the conference after running the Women's Tennis Association, is actually paid significantly more than his bosses. And those bosses run some of the largest and most prestigious universities in the country.

Scott makes far more than Oregon State president Edward Ray ($588,000) and Oregon's Michael Schill ($674,000). In fact, the commissioner makes more than any of the Pac-12 Conference head football coaches.

Scott is also paid more than Greg Sankey, the Southeastern Conference commissioner, who makes $1.9 million a year by comparison. Also, Scott makes more than Jim Delany, the Big Ten Conference commissioner, who brings home $2.4 million a year.

Sankey makes less than all 14 head football coaches in the SEC. He's out-earned by Alabama coach Nick Saban by more than $6 million annually. And Delany, in the Big Ten, earns about $5 million a year less than Michigan's Jim Harbaugh and makes less than all but two of the conference's head coaches.

Some of the athletic directors who have worked with Scott don't like him. That's not unusual for the gatekeeper in his position. He's not endeared to some of the football and basketball coaches, either.

Not unusual, either. His act has chapped media and fans at times, too.

But he has significant influence on the university presidents, or at least the core group that includes old-guard holdovers such as Oregon State's Ray, Arizona State's Michael Crow and UCLA chancellor Gene Block. And insiders will tell you that's how Scott maintains a foothold on his position despite swelling mistrust and discontent from the public.

The Pac-12 university presidents -- known as the "Pac-12 CEO Group" -- met in mid-November and reviewed budgets and discussed other matters. "No questions or concerns regarding the location of the conference offices were raised during our discussions," OSU's Ray said.

Ray also said: "I am comfortable with our present position with regard to Pac-12 operating costs."

By comparison, the SEC is headquartered in a 25-year-old, two-story building in Birmingham, Ala. The rent costs the conference $318,000 a year.

The Big Ten Conference office makes its primary home in suburban Chicago and also, has a satellite office in New York. Annual rent: $1.5 million.

The Pac-12 Conference headquarters cost the conference $6.9 million in rent in the last reported fiscal year. They're also carrying $11.7 million in deferred rent.

It's not just the headquarters real estate that cost the conference. Scott was hired in July 2009. Eight months later, records show he bought a 4,600-square-foot home on one acre in the upscale Blackhawk Country Club subdivision in Danville, Calif. Sale price: $1,850,000.

His initial contract with the Pac-12 included a $1,861,842 million relocation loan. That loan remains unpaid. Scott is required to pay it back in full.

The SEC's Sankey and his top-five compensated employees make a total of $3.9 million annually. Delany, from the Big Ten, and his top five lieutenants make $4 million.

The Pac-12 commissioner and his top-five salaried staffers rake in $8.4 million in annual compensation.

Andrew Walker, the Pac-12 Conference vice president of public affairs and head of communications, called the comparison between Power Five conferences "completely apples to oranges."

The Pac-12's defense lies in its position as an outlier: It's the only conference that owns and runs its own television network. Of the 112 full-time employees who work for the Pac-12, only 42 work for the conference itself. The rest are employed by the network. The SEC and Big Ten sell their media rights but aren't in the media-production business. The Pac-12 offices include 90,000 of square footage dedicated to studios, production bays, control rooms and a host of directors, technicians, equipment and talent.

Scott's role, the argument goes, is overseeing not just conference matters but the media network as well. There's a significant equity value attached to the network, sure, but that doesn't help pay the bills or get the Pac-12 into the lucrative football playoff.

When Washington reached the playoff in 2016, it was worth $450,000 to each of the Pac-12 Conference members. The conference itself also received an equal share.

Football produces the bulk of the revenue for big-time college athletic departments. And that's no different in the Pac-12, where football subsidizes a host of non-revenue generating Olympic sports.

The cost of maintaining its own television network is substantial. The failure to get distribution of the Pac-12 Network on DirecTV is a maddening issue for fans and coaches. Insiders say the ratings, guarded carefully by the conference, are a disappointment. There's private grumbling from ADs and coaches about less money and exposure compared to the other Power 5 conferences, but few will speak publicly. In part, because Scott has a reputation among staffers in the conference for being vindictive toward those who speak out against him.

Pac-12 Conference football coaches are the ones charged with winning football games and competing for the coveted College Football Playoff berths against peer programs that originate from the SEC and Big Ten.

"To think that college football at the top isn't an arms race is naive," Neuheisel said. "Those at the top need to have the bells and whistles."

Of the 16 teams to make the College Football Playoff in its first four seasons, only two have hailed from Scott's Pac-12 (Oregon in 2015 and Washington in 2016). Neither won a title.

Sankey's SEC has placed five teams in the playoff, including two national champions. Three Big Ten teams have made playoff appearances in Delany's tenure, and one of those won it all.

The Pac-12's choice to run its own network and lock into early distribution agreements has left the conference on the sidelines as others negotiated lucrative television rights deals and digital rights fees.

In the summer of 2017, the Big Ten announced a six-year deal with ESPN and Fox Sports worth $2.64 billion.

It's a game changer that is expected to net each Big Ten member a distribution of more than $50 million annually. Again, Pac-12 members received a $31 million distribution in the last fiscal year. It's left the conference having to make more from less. Consider, too, that Oregon State's athletic department is sitting on $40 million in accrued debt.

Many of the conference members are still footing the bill for large-scale renovations and expansions to their athletics facilities. Cal reported $18.7 million in debt-service payments in its fiscal year 2017. Washington had more than $16 million. Washington State ($10 million) and Colorado ($15 million) are also on the hook. And Oregon reported $19 million for the same period.

Earlier this season, Scott showed up at football media day in Hollywood and trumpeted the notion that the Pac-12 was well positioned for the next round of media rights' negotiations -- in 2024.

It landed with a thud.

Scott emphasized that during those negotiations the Pac-12 would be the only conference to own all of its rights (television and digital) free and clear.

Scott may be right -- but it may also prove to be too late. Consider that each SEC member stands to receive $10 million more annually from its conference headquarters than Pac-12 members in that span.

That's a minimum disparity of $60-million for each of the Pac-12 Conference members vs. SEC members over the next six seasons.

"The Pac-12 has to be really smart," Neuheisel said. "They've got to carve out more revenue so that USC and Washington, and those that are carrying the flag in the conference from a physical standpoint aren't completely dwarfed by these other teams anymore.

"The Pac-12 is trying to get one or two of those giant defensive linemen. Alabama and some of those SEC schools have 12 or 13 of those guys. You just can't compete unless you capture all the possible revenue."

Dave Bartoo, managing partner of Matrix Analytical Solutions, consults with some of the top football programs in the country. When asked if handing each member university even another $500,000 annually would make a significant difference, Bartoo offered a sobering thought.

"It could be the difference between your program getting a top offensive or defensive coordinator and missing out," he said. "Can we buy extra strength and conditioning coaches? Can we buy better nutrition? How about a better weight room?"

Bartoo believes those are questions the university presidents should be asking conference leadership.

Walker, the conference spokesman, replied: "We are confident that we are operating in a highly efficient manner, and our budgets are reviewed and approved by both our finance and audit committee and our full CEO Group."

---

Larry Scott boarded a Raytheon Hawker 800 chartered jet in Seattle at Boeing Field on Saturday, Oct. 20, and the eight-seat aircraft took off for Pullman, Washington.

Scott had just appeared in the press box at Husky Stadium at halftime of the Washington-Colorado game, and he'd soon face difficult questions during another halftime.

This one at Martin Stadium.

Washington State was up 27-0 on Oregon. But that's not what Scott would talk about. Instead, he'd be peppered by media during the intermission about blistering text messages sent by Cougars' coach Mike Leach regarding the instant-replay fiasco in the Sept. 21 WSU-USC game.

Leach called Pac-12 general counsel Woodie Dixon, "a coward." And he wrote to Dixon: "Why can't I help wondering if you're trying to manipulate wins and losses?"

Dixon - who is untrained in officiating -- called into the conference's Centralized Instant-Replay Command Center during the Sept. 21 game and overruled the replay officials on a controversial targeting call. The move raised questions about how often it previously happened, and eroded trust in the league's officiating.

Scott insisted Dixon "made a mistake" and called it an "isolated incident." And the commissioner scoffed when reporters in the press box said the actions hurt the trust and transparency the conference needed for its fans, players and coaches.

"My responsibility is to our members," Scott said at halftime of the Oregon-WSU game. "That's the trust and transparency."

Scott was specifically talking about serving his bosses, the Pac-12 CEO Group. But what about his obligation to fans? Ticket holders? And Pac-12 players and coaches?

"My obligation is to our members," Scott reiterated, "to uphold the highest level of integrity."

The conference vice president of communications, David Hirsch, stood off to one side listening to his boss. When it was over, Hirsch, a 23-year employee of the conference, settled back into his second-row press box seat to watch the second half of the game. He'd return to the Bay Area on a commercial airline the following day.

But Scott was already long gone. The chartered aircraft carrying the commissioner landed at Buchanan Field in the Contra Costa County airport well before the fans at WSU had even stormed the field, swarming quarterback Gardner Minshew, celebrating the Cougars' victory over the Ducks.

In a 24-hour period, the aircraft had traveled from Las Vegas to Phoenix to Seattle to Pullman to that small airfield not far from Scott's residence.

While the focus that weekend was on the officiating gaffe, the commissioner's travel schedule underscored another issue with the conference headquarters.

The SEC spent $788,000 on travel in the last reported fiscal year. The Big 10 spent $542,000 in conference travel expenses.

The Pac-12 Conference spent a total of $3.1 million. The Pac-12 will tell you this is, in part, because it's the only conference to run and own its own television network.

But when you examine the salary expenses, the rents, and the transportation costs, it makes you wonder why the Pac-12 didn't set up headquarters in Las Vegas, Salt Lake City or Phoenix. Also, the Pac-12 offers some employees a housing allowance as part of the compensation package due to the high cost of real estate in the region.

Said Neuheisel: "As beautiful as the offices are, it's a high-rent district. There are less expensive locations within the football footprint."

Walker, the Pac-12 Conference spokesperson, said Scott isn't to blame for that.

"The decision to situate the Conference headquarters in the San Francisco Bay Area as opposed to other member university markets was made by the Pac-12 CEO Group," he said. "This decision was made prior to Commissioner Scott assuming his role."

Walker is essentially right. The Pac-12 Conference office had long been located in Walnut Creek -- 25 miles east of San Francisco -- in a modest building with fewer than a dozen employees.

But it moved to the San Francisco location early in Scott's tenure and grew exponentially. Then-Pac-12 Enterprises president Gary Stevenson negotiated an 11-year lease on the downtown building owned by Kilroy Realty in 2011.

The Pac-12 Conference signed on to occupy two of the seven floors in the building. Stevenson told reporters at the time: "We love the vibrancy of San Francisco and believe it will be very conducive to the environment we envision."

Putting the headquarters in downtown San Francisco came at the insistence of Scott some say. He was interested in the high-rent address and the ability to network closely with tech-world executives.

"There are significant advantages from a recruitment perspective in attracting the best talent for a media company to be located in San Francisco, as opposed to in the suburbs or most other cities..." Walker said. "Additionally, there are advantages to being in the same location as a number of technology companies with whom we have existing or potential partnerships."

But those tech-company partnerships haven't flourished in the way the conference hoped.

In early November, the Pac-12 announced expanded partnerships with Audi and Jack in the Box, headquartered not in the Bay Area but in Virginia and San Diego, Calif. It also announced a new partnership with Texas-based Dr. Pepper and Maui Jim sunglasses, which is headquartered in Illinois. Late last year, the conference partnered with China-based Alibaba, to bring Pac-12 games to audiences in China.

The Pac-12 partnered with Twitter to stream nine events in late 2016 including the Harvard-ASU ice hockey game. The conference met with Facebook in the summer of 2016 and was invited to experiment with the social media company's video tool. It has worked with YouTube to create some content. However, the Big Ten Conference and SEC also have partnerships with the same social media partners.

That a lucrative Bay Area tech partnership hasn't materialized for the Pac-12 Conference is a sense of growing frustration.

---

The Pac-12 Conference benefited from a healthy cut of the proceeds to cover its own expenses in the last reported fiscal year.

It made those $31 million distributions to Oregon, Oregon State, and the rest of the conference members. But before that, the conference headquarters took $49 million off the top for "management and general expenses." It had total expenses of $139 million.

Which is only to say that the conference has done one thing exceptionally well inside that 113,000 square feet of office space - the Pac-12 offices have treated itself like the 13th and most important member.

Given that the Pac-12 continues to spend more than its peers on office rent, executive salaries and travel while raising less revenue, it's worth a deeper discussion. The conference is now faced with a second straight postseason in which it will not make the College Football Playoff. Part of that feels rooted in funding of the programs.

That it maintains its expensive travel, high-rent office space and Bay Area tech-industry salaries to do so makes you wonder.

Why not run a much leaner operation and give a larger distribution back to the members?

It's a question for the CEO Group, who we'd all hope examine the sports arm of their campuses with the same fiduciary scrutiny they dedicate to the rest of the operation.

To that, Dr. Ray at Oregon State said, "All of the CEOs are thoughtfully engaged in our discussions."

Where does the buck stop? Scott is the commissioner, charged like Sankey and Delany with putting the conference football programs in position to succeed.

Is it the CEO Group's responsibility? After all, it has oversight of Scott and doesn't appear motivated to change anything.

What about the Pac-12 football fanbase? Pac-12 fans don't show up 80,000 strong on any given Saturday, helping the conference print money. That's fact. But late-night kickoff times and poor television distribution haven't helped that cause, either. Allowing its network to set kickoff times, sometimes as little as six days before the game, has made it difficult on Pac-12 fans.

The Pac-12 Conference will never be consistently first tier in college football without financial parity. That's the current reality. And the conference is about to go into a six-year financial-disparity slide that will be difficult to overcome.

Neuheisel said conference leadership must improve.

"They can do better. There's no question they can do better," he said. "They keep thinking things will turn but it won't until they get players again.

"And that's not happening until they get money going."

The competition on the field depends on it. Is the Pac-12 Conference serious about winning? Does it have its act together behind the scenes? At least one conference coach wondered if executives were steering outcomes of games. So are they?

Like conference finances, it's worth a deeper examination.

On Wednesday, Part Two: Behind the Scenes at the Pac-12 Centralized Instant-Replay Command Center.